With Berlusconi tottering, Israel-Italy ties appear safe

ROME (JTA) -- Dogged by sex and corruption scandals, a revolt by former political allies, and WikiLeaks’ revelations that U.S. diplomats consider him “feckless” and a mouthpiece for Russian leader Vladimir Putin, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi is fighting for his political life.

A parliamentary confidence vote Dec. 14 may bring down the three-time prime minister's fractious center-right coalition and oust one of Israel's closest friends in Europe.

A collapse of the government next week should not have any immediate impact on relations between Italy and Israel, however. The two countries cooperate closely in a variety of fields, and Italy is among Israel's top economic partners in Europe. Any significant change in foreign policy would depend on whether early elections are called for the spring, and if so, what the outcome would be.

Berlusconi, 74, has a checkered record when it comes to Jewish issues. On the one hand, he’s been a strong supporter of Israel. Berlusconi has gone so far as to state that he "feels Israeli" and has called for Israel's inclusion in the European Union.

"Israel's security within its borders, as well as its right to exist as a Jewish state, is the ethical choice for Italians and a moral obligation against anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial," he said in a message to a pro-Israel rally in Rome in October.

At the same time, however, the prime minister is known for tasteless Holocaust-related gaffes. He was filmed this fall telling a joke about a Jew charging another Jew about $4,000 a day for hiding him during World War II. The punchline: "The Jew says, 'The question now is whether we should tell him Hitler is dead and the war is over.' "

In 2003, he angered local Jews with remarks that appeared to minimize the brutality of Italy's wartime fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini. But just days later, the Anti-Defamation League went ahead with a planned event honoring Berlusconi with its Distinguished Statesman Award.

"A friend is a friend even though he is flawed," ADL National Director Abraham Foxman told JTA at the time.

A billionaire media mogul who has dominated Italian politics since the mid-1990s, Berlusconi won a landslide victory in 2008 at the head of a center-right coalition that includes his center-right People of Freedom Party as well as the notoriously anti-immigrant Northern League.

With Berlusconi’s approval ratings now at an all-time low, he is battling opposition from the left and the right. His biggest immediate challenge comes from former ally Gianfranco Fini, 58, the speaker of the lower house of parliament, who is fighting Berlusconi in a bitter contest for leadership of the right wing.

Fini, also a staunch supporter of Israel, split with Berlusconi this summer, accusing him of corruption and anti-democratic party policies. Last month, Fini launched his own political party, Future and Freedom.

Fini, too, has a checkered past on Jewish issues. He is a former leader of the neo-fascist movement. But he broke with the far right a decade-and-a-half ago and since then has cultivated relations with Jews, visited Holocaust sites, publicly condemned fascism and even donned a kipah during his first trip to Israel in 2003.

"It is undeniable that Fini made big and probably sincere changes," said Annie Sacerdoti, the former editor of the Milan Jewish monthly Il Bollettino. But for some Jews, she said, “his past weighs on him.”

Italy is a highly polarized country, and to a large degree attitudes toward Berlusconi among Italy's 30,000 Jews are emblematic of general right-left political divisions.

Postwar Italian Jews tended to support the left. But in recent years the strong pro-Palestinian -- and in some cases virulently anti-Israel -- bent of much of the left has alienated growing numbers of Jews. This has translated into more support for Berlusconi and his right-wing allies at the ballot box.

"For some in the Jewish world, Berlusconi's unconditional support of Israel represents a guarantee that others do not give," Sacerdoti said. "He says he is a friend of Israel -- no ifs, ands or buts -- and this makes him credible to a part of the Jewish world.”

Yet many Italian Jews firmly oppose Berlusconi's overall politics. Some prominent Jews, including the left-wing member of parliament Emanuele Fiano, are active in an association called The Left for Israel, a group of politicians and others who support the Jewish state from a left-wing perspective.

Some critics describe Berlusconi's vocal backing of Israel as a functional friendship aimed at winning Italian and international Jewish support.

Berlusconi and his allies "are full of declarations of love for Israel, but they are indifferent to local Jewish issues,” said Rabbi Ariel Haddad, director of the Jewish Museum in the northeast Italian city of Trieste. “I am happy that they support Israel, but they seem to see Israel as the only Jewish issue.”

Whatever the motivation, the support for Israel has trickled down to the local level, in some cases in surprisingly high-profile ways.

Rome's right-wing mayor, Gianni Alemanno, was instrumental last year in having captured Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit declared an honorary citizen of the city, and a giant picture of Shalit hangs on the outside wall of Rome's city hall, the Campidoglio.

With Berlusconi struggling to retain power in the face of Fini’s political revolt, public dissatisfaction and sex scandals -- including allegations of "bunga bunga" sex parties and improper relations with teenage women, among them a Moroccan belly dancer known as Ruby Heart-Stealer -- Italian Jews soon may have to reconsider their political loyalties.

"Whether Berlusconi or Fini prevails, one looming question will be whether a modern, non-fascist Italian right can survive and achieve success without the questionable support of the far-right, xenophobic Northern League," said Francesco Spagnolo, an Italian Jewish scholar who works as a the curator of the Magnes Collection at a library at the University of California, Berkeley. "This will have repercussions."

Monday, December 13, 2010

Berlusconi article

My latest story on JTA is a news analysis of Silvio Berlusconi and the complicated political situation, from a Jewish angle.

Friday, November 12, 2010

RUTHLESS COSMOPOLITAN -- Start-up Continent

My latest Ruthless Cosmopolitan column on JTA once again attempts to demonstrate to the "outside world" that there is Jewish life in Europe.....

Startup continent: European Jewry

By Ruth Ellen Gruber · November 10, 2010

ROME (JTA) -- When I was in the United States recently, I gave a series of talks on contemporary Jewish life in Europe. One of my aims was to shed light on some of the creative new initiatives that are shaping the Jewish experience here, often against considerable odds and expectations.

"My eyes were opened to a Jewish world I had no idea existed," one woman told me.

Having written about the Jewish experience in Europe for many years, I sometimes forget how surprised people can be by developments that by now I take for granted.

Americans accustomed to viewing Europe through the prism of the Holocaust and anti-Semitism can be taken aback when they come face to face with such living Jewish realities as newly opened synagogues, crowded Jewish singles weekends and hip-hop klezmer fusion bands.

"American Jews don't tend to think about European Jewry often, and when we do, it is to lament its imminent demise, the victim of an aging, diminishing population and a sharply disturbing increase in anti-Semitism," Gary Rosenblatt, the editor of The New York Jewish Week, wrote this summer.

Some folks -- metaphorically I hope -- go so far as to express shock to find that a country such as Poland is "in color."

"Where had I seen Poland outside of World War II newsreels, Holocaust movies and photos, and, of course, 'Schindler's List'?" Rob Eshman, the editor of the Los Angeles Jewish Journal wrote last month after visiting Poland for the first time. "That entire movie was in black and white, except for the fleeting image of a tragic figure, a doomed little Jewish girl in a bright red dress."

The American Jewish challenge when it comes to modern Poland, he admitted, "is to reverse the 'Schindler's List' images, to see the country as mostly color, with a little black and white."

An optimistic new report now provides statistical backup for the bold new Jewish realities in Europe that I described in my talks.

Published last month, the 2010 Survey of New Jewish Initiatives in Europe aims to provide a "comprehensive snapshot" of Jewish startups -- that is, of "autonomous or independent non-commercial European initiatives" that have been established within the past decade.

"Conventional discussions of Europe often emphasize anti-Semitism, Jewish continuity, and anti-Israel activism," the survey's introduction states. "While we do not dismiss or diminish those concerns, we know that these are only part of the story. The European Jewry we know is confident, vibrant, and growing."

The findings are remarkably positive.

The survey presents data on 136 European Jewish startups and estimates that some 220 to 260 such initiatives are currently in operation, nearly half of them in the former Soviet Union and other post-communist states.

"There are more Jewish startups per capita in Europe than in North America," it says.

These initiatives, the study says, reach as many as 250,000 people, of whom about 41,000 are "regular participants and core members." They span a broad range of ages and affiliation, although European Jewish startup leaders and founders themselves "tend to affiliate with progressive and secular/cultural forms of Judaism."

Other findings reveal that the "vast majority" of these new Jewish initiatives are focused mainly on "Jewish education, arts and culture, or community building," and most of their financing comes from foundation grants and "grass-roots labor."

The survey was carried out by Jumpstart, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that promotes Jewish innovation, in cooperation with the British Pears Foundation and the ROI Community for Young Jewish Innovators based in Jerusalem.

I asked Shawn Landres, Jumpstart's co-founder, whether he thought the survey's findings presented a picture that was too rosy given the challenges still faced by European Jewry.

"I don't think the survey is overly optimistic," he told me. "The numbers of initiatives and the number of people involved (especially the otherwise unaffiliated) are accurate indicators of the creativity of European Jewry."

Still, he conceded, "the financial figures, especially the small budgets and low number of individual financial contributors, indicate just how fragile they are."

Landres noted that the demographic challenges facing European Jews -- long a hot topic for strategic planners -- were "complex." But, he said, they could not be reduced to "a single line in a single direction."

"Even if Jewish numbers in Europe are stagnating or declining overall, the threat or opportunity is in the details," he said. "What about intermarried families that identify as Jewish? What about the 80,000 or so people engaged by these new initiatives who have no other connection to the organized Jewish community? What about key population centers like London, Budapest, and Berlin that will remain Jewishly vibrant for generations to come?"

Landres said the fact that the survey showed nearly twice as many startups per capita in Europe as in North America "should challenge a few stereotypes."

But, he added, "I suppose it shouldn't have been surprising, given the number of respondents who feel that established institutions simply aren't making room for them and their peers."

Landres said all the initiatives analyzed in the survey were in operation as of this year, but he acknowledged that some may not last.

"Even so," he said, "projects need not be permanent to have impact, and the people involved frequently move on to other more successful Jewish communal endeavors armed with invaluable experience. Without risk and tolerance for failure, we cannot make transformative progress."

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Tablet Magazine -- Heym on the Range

Here's my recently story for Tablet Magazine about David Dortort, the creator of the iconic TV western Bonanza, who died Sept. 5. I had the pleasure and privilege of spending an afternoon with Dortort and his wife when I was the Visiting Scholar at the Autry National Center in December 2004, working on my continuing and ongoing project on the American West in the European Imagination.

Heym on the Range

By Ruth Ellen Gruber (Nov. 4, 2010)

Some years ago, when I first visited Sikluv Mlyn, a Wild West theme park in the Czech Republic, I was startled by the music piped in to the lobby of my hotel. It was the unmistakable theme song from the iconic TV show Bonanza–sung in Czech.

Bonanza, which ran from 1959 to 1973, recounted the adventures of the tight-knit Cartwright clan—the patriarch Ben, his three sons Adam, Hoss, and Little Joe—and the goings-on at their sprawling Ponderosa ranch. Syndicated to dozens of countries and dubbed into languages ranging from German to Japanese, it was one of the most popular and widely watched television shows of all time and has had a tremendous impact in honing the image of the American West around the world.

But few viewers realize how deeply rooted the show was in, well, Yiddishkeit (and not just because two of the stars—Lorne Greene as Ben and Michael Landon as Little Joe—were Jewish).

Bonanza was the brainchild of David Dortort, a pioneering television writer and producer who died in September at the age of 93. The Brooklyn-born son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Dortort had a lifelong commitment to Jewish causes; among other things, he and his wife Rose, who died in 2007, endowed cultural programs at the American Jewish University and Hillel at UCLA.

I discussed the Jewish underpinnings of Bonanza with Dortort during a lengthy interview at his home in Los Angeles in December 2004, as part of my ongoing research on the American West in the European imagination.

Bonanza’s story lines, he told me, centered on relationships rather than good guy-bad guy gunplay and stressed the values of love, respect, and family ties. He had employed these values, he said, to create a mythic world along the lines of the Arthurian legends, with the Ponderosa a sort of American Camelot and Ben Cartwright a King Arthur figure.

He named the Cartwright patriarch Ben after his own father, a yeshiva bokher who immigrated to the United States at 15 and became an insurance broker in Brooklyn. It wasn’t just a name that the two shared. “Essentially the values that I put into Bonanza are Jewish values that I learned in my home, from my father,” he told me. “One of the great things about the United States is that it’s probably the only country in the history of the world that can be described as a Judaic-Christian civilization. Where else did the Jewish people have the freedom they have in this country and enjoy the opportunities?”

Toward the end of our talk, Dortort shifted the conversation away from Bonanza. He told me a family story that shed light on how his own relationship to myth—and to the West—may have been shaped in part by the exploits of his Uncle Harry, a ne’er-do-well in the Old Country who wound up fighting alongside Pancho Villa in Mexico and battling anti-Semites on a California ranch.

In Dortort’s telling, Harry, his father’s younger brother, left Galicia in about 1916; he made his way to Hamburg and got a job on a ship. Soon, Dortort said, “he finds himself off the coast of Mexico and at a port called Tampico, on the Caribbean, and he hears about a fantastic guy in the interior, deep in the Sierra Madre, called Pancho Villa.”

Harry “jumps ship and makes his way into the Sierra Madre somehow to join Pancho Villa. He fights with Villa against the government of Mexico, and they became very close.” Harry, Dortort said, “was a tough little character. He was known as Pancho Villa’s Jew.”

According to Dortort, Harry was with Pancho Villa in March 1916 when Villa carried out a bloody raid on a U.S. Army garrison at Columbus, New Mexico. Soon after, Harry followed Villa’s advice and fled to Texas—specifically to San Antonio, where there was a Jewish community. There, Dortort recounted, Harry spied a woman on the porch of a house, brushing her long, black hair. “He knows this is a Jewish section of town, so he calls up to her in Yiddish, ‘Are you a Jew?’ And she looks down and says, ‘Yes, but who are you and what do you want to know for?’ He looks up and says, ‘Do you want to get married?’ And she hesitated a moment and said, ‘OK!’ ”

Harry and his bride headed west to California, where they operated a citrus ranch near Pomona. By 1920 or 1921, Harry had become so successful that he arranged for his brother Ben to bring his family out to California from Brooklyn.

Dortort was only 4 or 5 years old. “It was beautiful,” he recalled. “No smog in those days, the mountains were clear, and there was snow on them; southern California was like paradise.”

Nearly 40 years later, he created Bonanza.Read story at Tablet Magazine HERE

Saturday, October 16, 2010

Following in Gustav Mahler's footsteps in the Czech Republic

My latest piece in the International Herald Tribune/New York Times online:

On the Trail of Gustav Mahler

By RUTH ELLEN GRUBER

Published: October 15, 2010

KALISTE, CZECH REPUBLIC — I slept very well in the house where Gustav Mahler was born, waking in the morning to the bright sound of chirping birds in the trees outside my window.Once a shop and tavern run by the composer’s father, Mahler’s birthplace is now a snug, family-run pension whose amenities include a modern little concert hall as well as a cozy, wood-paneled pub.

Born on July 7, 1860, Mahler spent only the first few months of his life here before his family moved to the busy regional center of Jihlava, known in German as Iglau, about 30 kilometers, or 20 miles, away.

But Kaliste remains an essential stop for Mahler pilgrims, and I made the sleepy little hamlet my headquarters when I spent a late-summer weekend following the trail of the composer’s early life in the beautiful Vysocina highlands of Bohemia and Moravia.

This year and next mark two Mahler anniversaries: 150 years since his birth in Kaliste and, in May, 100 years since his death in Vienna.

Kicked off by a gala commemorative concert in Kaliste on Mahler’s birthday, the anniversaries are being celebrated with performances, festivals, exhibitions, publications, memorials, Web sites and other tributes.

I decided to visit the composer’s boyhood haunts as my own way of paying homage. The Vysocina region, about halfway between Prague and Brno, is one of my favorite parts of the Czech Republic — in Mahler’s day, of course, it formed part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Although he moved to Vienna at the age of 15 to study music, Mahler returned frequently for holidays and drew lasting inspiration from the landscape and local traditions.

“Mahler needs a remembrance of boyhood sights and sounds before he can write a note,” wrote the British critic Norman Lebrecht in “Why Mahler?: How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed the World,” a biography of the composer that came out this year.

Setting off from Kaliste, I followed narrow back routes through stately forests and rolling fields. Heavily laden apple and plum trees lined many of the winding roads, and goldenrod flecked the fields where corn stood tall, waiting for the harvest.

With Mahler’s symphonies playing loudly on the car stereo, I could easily appreciate how landscape and memory were powerfully reflected in the music.

“We would go for walks lasting half the day,” Mahler’s boyhood friend Fritz Lohr once recalled, “wandering among flowery meadows, by abundant streams and pools, through the great woods, and to villages where authentic Bohemian musicians set lads and lasses dancing in the open air.” I drove north to Ledec nad Sazavou, a small town on the Sazava River dominated by a soaring castle.

Mahler’s beloved mother, Marie, came from Ledec, and as a child, Mahler frequently visited his relatives there. The story goes that his grandfather Abraham Herrmann, a wealthy soap manufacturer, introduced the 4-year-old Gustav to music by letting him play an old piano stored in his attic.

Herrmann and his wife, Theresia, are buried side by side in the Ledec Jewish cemetery, a centuries-old graveyard that is reached through a gate from the municipal cemetery at the edge of town. The synagogue in Ledec — where some accounts say that the infant Gustav’s circumcision ceremony took place — still stands. Built in 1739, it was restored some years ago and now serves as a concert and exhibition hall.

From Ledec, it’s a 25-minute drive to Zeliv, a village at the confluence of the Zelivka and Trnava rivers. When he was a student, Mahler would come here on vacation to visit his friend Emil Freund, and it was in Zeliv that he had his first romantic involvement, with a cousin of Emil’s named Marie Freund.

Zeliv’s main attraction is a sprawling monastery complex, dominated by the majestic church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary. The monastery was closed down during the communist era, but religious life resumed in 1991, and today white-robed monks lead regular services in the ornate sanctuary of the church.

The little town of Humpolec makes a triangle with Zeliv and Kaliste. It was market day when I arrived, and I threaded my way through the stalls on the main square to get to the town museum, where a small permanent exhibition of photographs, documents and other material on Mahler opened in 1986.

Mahler’s paternal grandparents and other Mahler relatives are buried in the walled and tree-shaded Jewish cemetery, which lies just outside town in parkland beneath the ruins of the medieval Orlik Castle. The Freund family, including Marie, who committed suicide in 1880, also are buried here.

The Humpolec synagogue still stands near the center of town, but it now serves as a church. Jihlava, where Mahler lived from infancy until he left to study in Vienna in 1875, was my last stop on this exploration of his youth.

Many specific sites in the town are connected with Mahler’s boyhood and family life: the towering St. Jakub Church is said to be the where Mahler, who converted to Roman Catholicism in 1897, first heard a Mass.

The house at 4 Znojemska, where the family lived, is just a few steps from the large and graceful main square — which today is somewhat blighted by a modern commercial structure in its center.

The Mahler house now serves as a museum that focuses on his family and his relationship with Jihlava and the surrounding region, as well as on the Czech, German and Jewish traditions that made up the cultural landscape of his time.

Mahler’s parents are buried in the Jewish cemetery, but the synagogue was destroyed by the Germans in 1939. The ruins of its foundations have now been incorporated into what is called Gustav Mahler Park, a rather jarring sculptural arrangement reminiscent of Stonehenge that centers on a bizarrely attenuated statue of the composer.

The park was opened this summer as part of Mahler anniversary celebrations. The day I visited, a bride and groom were using it as a backdrop for their wedding photos.

More information is online. For the Czech Mahler Trail, go to gustavmahler2010.cz; the Mahler Pension in Kaliste, mahler-penzion.cz/en/; and the Mahler House Museum in Jihlava, mahler.cz/en/

Friday, September 24, 2010

Article -- Calabrian village honors Philadelphia artist

I have an article in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent about the opening of the permanent exhibition of my mother's art work in Nocara, Calabria.

Italian Village Honors Work of Philly Artist

September 23, 2010

Ruth Ellen Gruber

Jewish Exponent Feature

NOCARA, Italy

During the 1970s and '80s, my parents spent considerable chunks of time in southern Italy, documenting local life in Nocara, a wind-swept Calabrian village that clings to the crest of a half-mile-high hill overlooking the Gulf of Taranto.

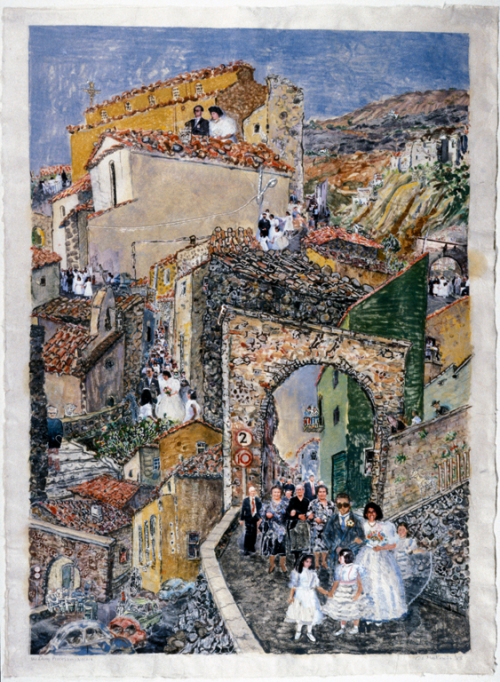

Shirley Moskowitz

My father, Jacob W. Gruber, was an anthropologist at Temple University, and was there to carry out an ethnographic study. He visited peasant homes and observed local events, interviewed and photographed people, and took reams of notes about local customs, traditions and beliefs.

My mother, the artist Shirley Moskowitz, recorded village life her own way.

Setting up her easel in odd corners of the town, she painted dozens of landscapes, townscapes and portraits that keenly captured both the harshness of the sunbaked uplands and the living face of a village that was just emerging from an age-old traditional lifestyle into modernity.

My mother died in 2007.

This past August, on what would have been her 90th birthday, Nocara honored her memory and her creativity by opening a permanent exhibit of some 40 of her artworks in the main chamber of the local town hall.

My father, who is now 89, and my brother, Sam, flew to Italy, and together we drove eight hours south from my home in Umbria to be guests of honor at the opening ceremony.

As we walked through Nocara's narrow streets, Dad was accosted by villagers who remembered "il professore" and my mother from the old days. Some of them now are middle-aged adults whose likenesses my mother had drawn when they were children.

Many angles of town leaped out at us as if from one of Mom's paintings: a rough stone archway, the flat face of a chapel in its little piazza, steep stone lanes and tiled roofs.

Much has changed, of course. Pigs no longer graze in Nocara's streets, as I recall seeing them do when I visited my parents there decades ago. And donkeys are no longer a major means of transport. Moreover, Nocara now has gas, running water and other modern utilities, including Internet access.

A Posthumous Thanks

"Shirley Moskowitz's paintings represent a piece of Nocara, at a special time in its history," Mayor Franco Trebisacce told the several dozen people who attended the ceremony. "We have an obligation to display them here, and to offer our posthumous thanks to an artist who loved this town, and to her family."

The exhibit, in fact, was a long time coming.

Synagogue collage by artist Shirley Moskowitz

My parents had donated Mom's art works to Nocara a decade ago.

The gift had made headlines in local newspapers at the time, but the works were never permanently displayed, and for the past eight years or so they had languished in storage, almost forgotten.

Mayor Trebisacce, who came to office last year, remembered them, however, and became curious about their fate. Earlier this summer, he and his aides found them in a closet, packed away in their original shipping case.

A Google search took them to the Web site that my family had created about my mother's art after her death -- shirleymoskowitz.wordpress.com -- and they contacted us by leaving a comment on the site.

Many of the works that Mom donated to Nocara had already been exhibited at several major shows in Philadelphia, including a landmark retrospective at the University of the Arts in 1996 that had showcased more than half-a-century of my mother's life in art.

Her work encompassed a variety of media -- from simple line drawings and sketches to sculpture, oils and the joyously complex, multilayered collages that, since the 1960s, had become her signature style.

Some of her paintings and drawings now on display in Nocara, in fact, formed the basis of several of her major collages, such as "Wedding Procession," dating from 1988.

Looking back, Mom was an intensely Jewish artist, but not a "Jewish artist," per se.

She never created Jewish ritual art, though she frequently turned to Jewish themes and subject matter.

One of her first sculptures, dating from 1942, is a study of a huddled man and woman called "Refugees," and other sculptures, prints and paintings depict a cantor, a rabbi, Jewish holidays and life-cycle events, even a solemn moment from the Aleinu prayer.

A collage she created as a sort of multi-textured self-portrait prominently included Shabbat candlesticks, even though she herself was not observant.

And following a trip she took with me in Eastern Europe in 1992, she produced a particularly powerful series of monotype prints of some of the ruined synagogues and Jewish cemeteries that we visited.

But these -- like her Judaism itself -- were all part of the much broader kaleidoscope of her life. Her work, in fact, embraced and reflected the wide variety of landscapes, friends, family and experiences that made up her world.

Her collages in particular mixed dreams and reality to project a richly textured vision of life as she lived and perceived it, among her family, friends, neighbors and the local environment.

As she once put it, they were based "on personal experience and are composed to affect the viewer from a distance while at the same time inviting him to participate in the action -- to experience through color, dynamic contrasts of light and dark, and various techniques, a reality that may seem fantastic but is still real."

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Ruthless Cosmopolitan -- Savoring "goulash Judaism" in Budapest

|

| Sharansky nails a mezuzah to the doorpost of the new Israeli Cultural Institute in Budapest. Photo (c) Ruth Ellen Gruber |

My latest "Ruthless Cosmopolitan" column for JTA recounts some of my experiences at Rosh Hashanah this year in Budapest. A lot more was going on of course, but I would have needed a clone....

Savoring "goulash Judaism" in the Hungarian capital

By Ruth Ellen Gruber

JTA -- Sept. 16, 2010

BUDAPEST (JTA) -- I always try to spend at least part of the High Holidays in Budapest, so I can sample some of the spicy mixture that characterizes the Jewish experience in the Hungarian capital.

As many as 90,000 Jews live in Budapest, the largest Jewish population in any central European city. The vast majority are unaffiliated -- and probably always will be.

Those who do identify as Jews, however tenuously, have an evolving choice of public and private, religious, cultural and secular ways to express or explore their identity.

Gastronomic, too: This year, one friend made challah for the first time to serve at the holiday dinner, and a downtown restaurant even offered a special Rosh Hashanah menu.

Call it "goulash Judaism," if you will -- a simmering mix whose disparate, and often fractious, components combine to form a highly seasoned whole.

Events and observances this year bore witness to the growing array of Jewish options, both inside and outside traditional settings.

The week leading up to Rosh Hashanah, for example, saw the conclusion of the city's 13th annual Jewish Summer Festival, a 10-day series of performances and other events, including a book and crafts fair, that drew thousands of visitors. Also that week, an ambitious Israeli Cultural Institute opened in a refurbished building at the edge of the main old downtown Jewish quarter.

And further afield, in the Obuda district in the northern part of the city, a 190-year-old synagogue that had been used for decades as a state TV studio was rededicated as a Jewish house of worship.

Rented from the state and restored by Chabad, the synagogue will form part of Chabad's growing local network.

Foreign VIPs were in town for all three occasions.

The Jewish Summer Festival culminated with a well-publicized concert by the Chasidic reggae rapper Matisyahu in a major city event arena.

Jewish Agency Chairman Natan Sharansky affixed the mezuzah to the doorpost of the Israeli Cultural Institute, which was largely funded by the agency. Institute director Gabor Balazs said the institute's aim was to introduce and popularize Israel's "mosaic-like" culture to the Jewish and non-Jewish public at large.

And Israel's Ashkenazi chief rabbi, Yonah Metzger, joined Chabad rabbis in cutting the ribbon at the Obuda synagogue.

"This is the best possible answer to what the Nazis did," Metzger told the crowd of 1,000 or more, including Hungarian government and religious leaders, attending the ceremony. "Fifty years after the last time Rosh Hashanah was celebrated here, it will be celebrated here once again."

My own holiday observances also reflected new choices.

I usually attend High Holidays services at one of the 15 or so mainstream synagogues active in Budapest, or sometimes I "synagogue hop" to two or three shuls. Most of them belong to the Neolog movement -- the Hungarian variant of Reform Judaism that is the country's dominant religious stream. But there are also several traditional Orthodox synagogues, as well three or four now affiliated with Chabad.

This year I chose to avoid the mainstream. I sampled Rosh Hashanah services at two small alternative groups -- Bet Orim, one of Budapest's two American-style Reform congregations, and Dor Chadash, a young people's minyan associated with the Masorti, or Conservative, movement.

As neither Reform nor Masorti is recognized by the Hungarian Jewish Federation, both operate outside the umbrella of establishment Jewry.

Bet Orim celebrated a formal service in the auditorium of the Budapest JCC, while Dor Chadash held a more informal gathering in the living room of the local Moishe House, a downtown apartment that serves as a combination residence and center for Jewish educational encounters.

Each group numbered about 30 or 35 people, and both offered an American-style egalitarian Jewish prayer experience that is alien to mainstream Hungarian Jewry.

At Bet Orim, in fact, a young woman named Flora Polnauer served as the cantor for High Holidays services.

"It's the first time that a Hungarian Jewish woman has fulfilled this role," Bet Orim's rabbi, Ferenc Raj, told me proudly.

Raj, a native of Hungary, moved to the United States decades ago and is rabbi emeritus of Congregation Beth El in Berkeley, Calif.

"We are making history tonight," he said.

I had met Polnauer before under quite different circumstances. The daughter of a rabbi, she sings with several local music groups, including hard-driving Jewish hip hop bands.

During the service, dressed in white, she chanted the familiar melodies in a lilting voice. But she looked a little nervous and was clearly moved by the experience.

"I really feel we deserve the Shehecheyanu!" she exclaimed at the end, referring to the blessing recited to mark special occasions and moments of joy.

We all joined in and chanted it with her: "Blessed are you, O Lord, our God, sovereign of the universe who has kept us alive, sustained us, and enabled us to reach this season."

Wednesday, September 1, 2010

European Day of Jewish Culture

My latest JTA article deals with the annual European Day of Jewish Culture -- a topic I have written about on a fairly regular basis in the 11 eleven years since it was established. Indeed, I took part in the meeting in Paris in 1999 when it was decided to expand the regional "open doors" to Jewish heritage events in Alsace into an international initiative.

Despite being in its 11th year, the "Day" is still fairly unknown -- except in a few places, such as Italy, where it has become a high-profile event on the end-of-summer calendar, with lots of media coverage and support from state and local authorities.

Despite being in its 11th year, the "Day" is still fairly unknown -- except in a few places, such as Italy, where it has become a high-profile event on the end-of-summer calendar, with lots of media coverage and support from state and local authorities.

Tourists shop in a store in the former Jewish district of Pitigliano that sells kosher wine, matzah, Jewish pastries and souvenirs. Photo (c) Ruth Ellen Gruber

Introducing non-Jewish Europeans to Jewish life

By Ruth Ellen Gruber · August 31, 2010PITIGLIANO, Italy (JTA) -- In Italy, where there are only about 25,000 affiliated Jews in a population of 60 million, most Italians have never knowingly met a Jew. "It's unfortunate," said the Italian Jewish activist Sira Fatucci, "but in Italy Jews and the Jewish experience are often mostly known through the Holocaust."

Fatucci is the national coordinator in Italy for the annual European Day of Jewish Culture, an annual transborder celebration of Jewish traditions and creativity that takes place in more than 20 countries on the continent on the first Sunday of September -- this year, Sept. 5.

Synagogues, Jewish museums and even ritual baths and cemeteries are open to the public, and hundreds of seminars, exhibits, lectures, book fairs, art installations, concerts, performances and guided tours are offered.

The main goal is to educate the non-Jewish public about Jews and Judaism in order to demystify the Jewish world and combat anti-Jewish prejudice.

“What we are trying to do is to show the living part of Judaism -- to show life," Fatucci said. "What we want to do is to use culture as an antidote to ignorance and anti-Semitism.”

Some 700 people flock to Culture Day events each year in Pitigliano, a rust-colored hilltown in southern Tuscany that once had such a flourishing Jewish community that it was known as Little Jerusalem. Most local Jews moved away before World War II, and today only four Jews live here in a total population of 4,000. But in recent years the medieval ghetto area has become an important local attraction. The town produces kosher wine, and a new shop sells souvenir packets of matzah and Jewish pastries.

Culture Day events here include kosher food and wine tastings, guided tours, art exhibits and an open-air klezmer concert.

"There's a lot of ignorance, but a lot of curiosity about Jews," said Claudia Elmi, who works at Pitigliano's Jewish museum, which opened in the 1990s and now attracts 22,000 to 24,000 visitors a year -- the vast majority non-Jews. "But the Jews were seen as closed, or even physically closed off," she said. "The open doors of the Day of Culture are very important."

Tourists line up to tour the Jewish museum and the synagogue, a 16th-century gem that fell into ruin following World War II and was rebuilt and reopened in 1995. They make their way down steep stairs into the former mikvah and matzah bakery, which are located in rough-hewn subterranean chambers carved into the solid rock.

"We didn't know anything about Judaism before coming here," said Rosanna and Paolo, tourists from Padova who visited Pitiligano's Jewish sites a week before Culture Day. "We learned a lot here, particularly about the religious rituals and kosher food."

Now in its 11th year, Culture Day is loosely coordinated by the European Council of Jewish Communities, B'nai B'rith Europe and the Red de Juderias, a Jewish tourism route linking 21 Spanish cities. Countries participating this year include Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, France, Germany, Britain, Italy, Holland, Norway, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. This year’s theme is "Art and Judaism."

Each country makes its own programs, and depends on local resources and volunteers to host, plan and carry out activities. Thus in some countries, only a few events take place: Norway will have a klezmer concert and lecture in Oslo; Bosnia has only an art exhibit in Sarajevo. Elsewhere, a varied feast may stretch for several days. In Britain, this year's activities last until Sept. 15 and include dozens of events in London and more than 20 other cities.

Jewish art "is both distinctive and universal" said Lena Stanley-Clamp, the director of the London-based European Association for Jewish Culture. "It certainly speaks to and is enjoyed by people of all backgrounds."

Italy is by far the European Day of Jewish Culture's most enthusiastic participant. Thanks to Fatucci and her army of volunteers and communal organizers, it has grown to become a high-profile fixture on the late-summer calendar, with events and activities up and down the Italian boot.

Last year's events attracted 62,000 people -- about one-third the total number who attended Jewish Culture Day events around the continent and about twice the number of Jews in Italy. This year, activities are being staged in 62 towns, cities and villages, including many places -- like Pitigliano -- where few or no Jews live.

"There is a great curiosity about Jews and Jewish culture here, so the opportunity to engage in a Jewish cultural activity is very attractive," Fatucci said. "The Day of Jewish Culture became a reference point for this."

Part of the success, she said, was due to the fact that Culture Day in Italy is so well organized and publicized. Jewish communities work closely with public and private institutions, and the event receives government support and recognition.

But, Fatucci added, Jewish heritage in Italy encompasses a remarkably rich and varied array of treasures -- Roman-era Jewish catacombs in Rome, medieval mikvahs, Baroque synagogues, and the historic ghetto and centuries-old Jewish cemetery in Venice.

"Italy is the country of art, par excellence," Fatucci said. "But in many places, people have lived side by side with fragments of Jewish culture without knowing anything about them -- or even knowing they were there."

(For a program of European Day of Jewish Culture events, visit Jewisheritage.org.)Read full article at jta.org

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Symposium and Exhibit in Nocara, Calabria

Here's a crosspost from the Shirley Moskowitz web site -- a brief report on the symposium and opening of a permanent exhibit of my mother's art work in the remte village of Nocara, Calabria, last week. You can see other posts at the web site.

Nocara — Exhibit Opening and Conference

August 6, 2010 by ruthellengruber | Edit

The event in Nocara August 4 opening the permanent exhibit of works that Shirley Moskowitz did there in the 1970s and 1980s and donated to the village 10 years ago was a great success – and lots of fun. The art works — townscapes, landscapes and portraits, mainly in watercolor, ink or pencil — are hung in the Town Council meeting room, and this, says Mayor Franco Trebisacce, is where they will remain, as a testament to the history of the village at a time when it was just on the verge of change from the age-old traditional lifestyle to modernity.

The speakers — two professors from the University of Cosenza and Vincenzo Salerno, the former longtime mayor of Nocara — discussed both the context of the works as well as the development of the village and the importance of the collection, and what it represents, for the town. Salerno recalled that Mom and Dad visited Nocara for lengthy periods of time over several years, at various seasons of the year. He noted that back then, it was still a largely peasant society, where donkeys were used for transport and animals were kept in town. Few men under retirement age lived in town, as most had immigrated northward to find work. Sam then spoke about the art itself. And we were presented with an engraved plaque as thanks for Mom’s work.

Dad gave a very moving little speech about Mom and her life as an artist — I recorded it and will try to post as an mp3.

There was an enthusiastic turnout, including a number of people who remembered Mom and Dad from the old days. Many people came up to Dad to reminisce — and Dad’s Italian rose to the occasion. The few people I knew from my own two visits to Nocara many years ago were there — and even to me recognizable, including Vincenzo Salerno, his brother Cici, and Giuseppe and Maria De Mateo.

There were several people in attendance who now, as adults, were able to see the portraits Mom did of them as children. Few of these people still live in Nocara (though some were back for summer vacation). Ernesto (shown here) is one of the few younger people who still lives in the town. We kept hearing over and over that Nocara is now was just “a town of old people.”

The event kicked off the annual summer pork festival (Festa del Maiale) — and the evening concluded amid an outdoor grilled feast, loud music, and dancing in the piazza. (Including with Cici Salerno — with whom I remember dancing in the piazza in 1981!)

The festival culminates with a big religious procession of the Madonna on August 15, either to or from the old monastery chapel of Santa Maria degli Antropici way down a very winding road from the village.

The speakers — two professors from the University of Cosenza and Vincenzo Salerno, the former longtime mayor of Nocara — discussed both the context of the works as well as the development of the village and the importance of the collection, and what it represents, for the town. Salerno recalled that Mom and Dad visited Nocara for lengthy periods of time over several years, at various seasons of the year. He noted that back then, it was still a largely peasant society, where donkeys were used for transport and animals were kept in town. Few men under retirement age lived in town, as most had immigrated northward to find work. Sam then spoke about the art itself. And we were presented with an engraved plaque as thanks for Mom’s work.

Dad gave a very moving little speech about Mom and her life as an artist — I recorded it and will try to post as an mp3.

There was an enthusiastic turnout, including a number of people who remembered Mom and Dad from the old days. Many people came up to Dad to reminisce — and Dad’s Italian rose to the occasion. The few people I knew from my own two visits to Nocara many years ago were there — and even to me recognizable, including Vincenzo Salerno, his brother Cici, and Giuseppe and Maria De Mateo.

There were several people in attendance who now, as adults, were able to see the portraits Mom did of them as children. Few of these people still live in Nocara (though some were back for summer vacation). Ernesto (shown here) is one of the few younger people who still lives in the town. We kept hearing over and over that Nocara is now was just “a town of old people.”

The event kicked off the annual summer pork festival (Festa del Maiale) — and the evening concluded amid an outdoor grilled feast, loud music, and dancing in the piazza. (Including with Cici Salerno — with whom I remember dancing in the piazza in 1981!)

The festival culminates with a big religious procession of the Madonna on August 15, either to or from the old monastery chapel of Santa Maria degli Antropici way down a very winding road from the village.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Ruthless Cosmopolitan -- Shabbatons for non-Jews in Poland

My latest Ruthless Cosmopolitan column for JTA is about how a "public display of Judaism" is being used in a country where the Jewish presence dwarfs the actual number of Jews who live there.

In Poland, Shabbatons for non-Jews to combat anti-Semitism

By Ruth Ellen Gruber · August 2, 2010PIOTRKOW TRYBUNALSKI, Poland (JTA) -- Whenever I visit Poland, I'm struck by how the intensity of the Jewish presence dwarfs the tiny number of Jews who actually live in the country.

Even with the resurgence of Jewish life since the fall of communism, organized Jewish communities exist in fewer than a dozen Polish cities, and only the Warsaw community numbers much more than a few hundred people.

Yet each year sees hundreds of Jewish-themed festivals, conferences, educational projects, commemorative activities, publications and other initiatives throughout the country.

"I often joke that the mayor of every small town now feels obliged to make excuses if he or she has no Jewish festival," said Anna Dodziuk, a Jewish activist in Warsaw. Dodziuk published a book this year on Poland's largest and most famous Jewish festival, the nine-day Festival of Jewish Culture in Krakow, which has been going strong since 1988. "To put it in short," she said, "it is politically correct now to explore the Jewish history of the local communities, to commemorate Jews of a shtetl who perished in Holocaust, to celebrate somehow Jewish culture."

The activities are meant to educate and memorialize, but they coincide with a Jewish presence that is glaringly visible in more negative contexts, too, and this is also part of the paradox.

Anti-Semitic graffiti is shockingly widespread. Spray-painted Stars of David hanging from gallows deface countless walls.

Much of this, however, likely has little to do with actual Jews. The ugly scrawls are the work of soccer fans who may have no idea what Judaism is but have adopted Jewish symbols as pejoratives with which to bash their opponents.

Meanwhile, figurines of Orthodox Jews clutching coins fill souvenir stalls in Warsaw, Krakow and some other cities. The imagery harks back to the stereotype of Jews as greedy moneylenders, but the figurines are marketed today as abstract good-luck talismans.

"When a member of the city council from a Polish town came to visit me in the States not long ago, he brought a present," said Michael Traison, an American Jewish lawyer who has offices in Chicago and Warsaw. "It was a painting of a Jew counting money, with a dollar bill stuck in its back. He obviously had no idea that the image could be offensive."

Trying to make sense out of the disparity is a cottage industry among scholars, educators, policymakers, communal leaders and ordinary citizens.

How do you balance an abstract evocation of Jews and Jewish life with the real thing? And how do you prevent stereotypes and skewed templates from dominating discourse?

Traison believes a sort of "public display of Judaism" can be useful.

Toward that end, over the past four years he has helped organize Shabbatons that have brought actual Jews and Jewish practice to half a dozen provincial towns where few or no Jews have lived since the Holocaust. Religious services are held in long-disused synagogues, and local officials and ordinary citizens are invited to join in for prayers, kosher meals and Shabbat study.

Traison says he has four main goals: remembrance; demonstrating that the Jewish people -- and Judaism -- are still alive; outreach to Poles; and enabling Jews and local Catholics to participate in a Jewish religious experience.

"This is all very important for young people in Poland, who often only know Jews through imagery and mythology," he said.

Stanislaw Krajewski, a Warsaw Jew who has attended several of the Shabbatons, agreed. "It doesn't just show pictures but is doing something that is really alive," he said. "It is such an innovation -- a way of bringing a sort of circulation of blood in these places."

A Catholic man who attended last year's Shabbaton in Kielce put it this way: "I could feel myself what I already knew theoretically, namely what the Shabbat means for Jews who treat their faith seriously.”

The song “Boi Kala” – “Come, Sabbath Queen” – “is also a challenge or a question on how I, a Christian man, treat my 'shabbat’ -- Sunday," the man said. "Thanks to Jews' testimony of how they treat their holy day, I treat my one more seriously."

Most of these elements were evident at the latest Shabbaton, which took place this summer in Piotrkow Trybunalski, a rundown industrial town in central Poland where city walls are scarred by anti-Semitic soccer graffiti but also bear commemorative plaques recalling the town's rich Jewish past.

The Shabbaton coincided with a city-sponsored Days of Judaism festival, and posters advertised the religious events along with lectures, exhibits and a klezmer concert. Piotrkow's mayor and other officials took part in a Holocaust commemoration ceremony, a kosher Shabbat dinner and an open-air Havdalah celebration in a public park near the center of town.

Schoolchildren staged a play based on a Holocaust story, and Poland's chief rabbi, Michael Schudrich, led services in Piotrkow's former synagogue, which was defiled by the Nazis and then turned into the public library in the 1960s.

Most of the participants were Piotrkow Holocaust survivors and descendants from Israel, the United States and other countries. They included the former Israeli diplomat Naftali Lau-Lavie, who was called to the Torah that Shabbat to celebrate the 71st anniversary of his bar mitzvah. Lavie's father was Piotrkow's last chief rabbi, and his brother is Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau, a former Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel and now the chief rabbi of Tel Aviv.

Many in the group had visited Piotrkow before. Some had sponsored commemorative projects such as placing plaques and cleaning up the Jewish cemetery. They came to honor the dead, relive memories and make a positive statement simply by walking the streets.

It was "surreal" to pray where both "fame and infamy reigned," said Irving Gomolin, a survivors' son from Mineola, N.Y., who was making his third trip to Piotrkow. But, he added, "It also helps send the message to the town that we have not forgotten, that the Jewish nation and Piotrkower Jews survive and remember and do not want to forget or have their past in this place forgotten."Read story at JTA.org

Friday, July 23, 2010

Budapest -- Progressive Jewish Music Scene

My latest JTA piece explores the progressive Jewish music scene in Budapest, ahead of the Bankito Festival in August. I have blogged about some of these people in the past on my Jewish Heritage blog.

Read story at JTA.org

Jewish fusion music key to Budapest’s ‘Jewstock’ festival

By Ruth Ellen Gruber · July 22, 2010

BUDAPEST (JTA) -- Flora Polnauer, 28, tilts back her head, half closes her eyes and hums a few bars of a song by her hip-hop/funk/reggae band HaGesher.

The song is "Lecha Dodi," the Shabbat evening prayer -- sounded over a Yiddishized version of the Beatles song "Girl." It's just one of the many unconventional songs of the band, whose vocalists rap their own lyrics in Hebrew, Hungarian and English.

"It's modern Jewish music because it's influenced by Jewish things, but it's not the replaying of old Jewish songs," says Daniel Kardos, 34, a composer and guitarist who plays with Hagesher and several other bands. "I pick up many things and mix them."

Hagesher is one of about half a dozen bands in this city of European Jewish cool blending jazz, hip hop, rap and reggae with Israeli pop and traditional Jewish folk tunes and liturgy to form an eclectic urban sound.

"It's a big mix of contemporary Jewish musical identity," said vocalist Adam Schoenberger, the son of a rabbi. "All of us find Jewish culture very important. Hagesher is a platform for us to articulate musically our different musical interpretation of Jewish cultural heritage."

As the program director of the popular Siraly club, whose dimly lit basement stage is a regular venue for Hagesher and other groups, Schoenberger, 30, is a leader in Budapest's Jewish youth scene. He is also one of the organizers of Bankito, sometimes referred to as "Jewstock" -- a youth-oriented Jewish culture festival Aug. 5-8 on the shore of Bank Lake, north of Budapest.

Bankito includes concerts, exhibitions, performances, workshops, seminars and lectures, a poetry slam, sports events, movies, and Jewish and interfaith religious observances. A number of events at this year's festival will highlight Roma, or Gypsy culture, and focus also on social and civic issues such as the rights of the Roma and other ethnic minorities.

Music is a highlight of Bankito. Hagesher, the Daniel Kardos Quartet and other Jewish bands such as Nigun and Triton Electric Oktopus will perform. "We're at a fascinating moment in Jewish music: It's hip again," said Michigan's Jack Zaientz, who authors the Teruah Jewish music blog. "There's an amazing gang of musicians who are young, smart, urban and Jewish, and making their Jewish identities a core part of their music and stage identities."

The Budapest musicians take their cues from Jewish bands in North America, Paris, London and elsewhere that also experiment with new forms and fusions. Among their models are John Zorn, the avant-garde composer who has promoted "Radical Jewish Culture" on his Tzadik label since 1995, DJ Socalled and Balkan Beat Box, and Orthodox reggae star Matisyahu and rapper Y-Love.

Trumpeter Frank London, who regularly tours Europe with the Klezmatics and other bands, has had a particularly strong impact with his mash-ups of klezmer, Balkan brass and even Gospel.

"Everyone is influenced by Frank London through the Klezmatics," said Bob Cohen, a Hungarian-American musician and writer who has lived in Budapest since the 1980s. "But another big influence in Hungary is Israeli raves on Tel Aviv beaches."

"I played at Jewstock a couple of years ago," Cohen said. "People there had an academic interest in klezmer, but what they want is to go out and rave."

In some ways, Cohen said, the new Jewish music scene in Budapest developed as a reaction to a more traditional klezmer music scene that many young people now perceive as part of the stuffy mainstream establishment. The Budapest Klezmer Band, for example, the city's best-known Jewish music group, performs internationally in opera houses and concert halls as well as theaters and mainstream festivals. Formed in 1990, the band also collaborates on elaborate klezmer stage productions and ballets.

"The new Jewish music scene is a party scene, not a concert scene, and the older generation doesn't relate to it," Cohen said. "In a way, they want an art form that won't be understood by the traditional Jewish establishment."

In many ways, Kardos exemplifies both the musical variety and the variety of influences that help shape the scene.

In addition to Hagesher and his own quartet, he composes film music and plays with several other bands. One of them, Shkayach, is a collaboration with Polnauer, a rabbi's daughter and powerful vocalist who raps with Hagesher and other groups. Shkayach forms a contrast with their rap and progressive jazz work by creating an intimate acoustic sound based on traditional Yiddish and Israeli melodies.

Kardos attended a Jewish high school in Budapest and made aliyah after graduation. In Israel, he learned Hebrew and studied jazz at the Rubin Academy of Music in Jerusalem. But like many young Hungarian Jews who moved to Israel in the 1990s, he decided after three years to return to Hungary, where he continued his studies.

It was only back in Budapest, Kardos said, that he realized the importance to him of both Jewish music and his own Jewish identity. "It was strange because when I was in Israel, I wasn't open so much to the Jewish musical traditions," he said. Away from Israel, though, Kardos said that "I realized that it was more important than I thought. I was very young when I was in Israel, and I didn't realize that it's very important to be Jewish and have all these traditions."

He added, "I think I was too young for the music, too. After some time I realized that when I hear those Eastern melodies, I just feel like home. It's so natural to me. Like being in a swimming pool and floating.

Read story at JTA.org

Monday, July 19, 2010

Conference on Shirley Moskowitz's art in Calabria

I'll be going to Calabria in a couple of weeks, with my dad and my brother Sam, for a conference on the art work my mother did in the small village of Nocara in the 1970s and 80s.

Here's a cross post from the shirleymoskowitz.wordpress.com web site --

Here's a cross post from the shirleymoskowitz.wordpress.com web site --

A conference on the art work that Shirley Moskowitz did in the 1970s and early 1980s in the small town of Nocara, in Calabria, will be held in Nocara on August 4 — which would be Shirley’s 90th birthday. It is being organized by the Mayor of Nocara and the local authorities.

I don’t have all the details yet, but it will be a one-day event, that afternoon/evening, with a speaker from the University of Cosenza.

Shirley spent several periods of time painting in Nocara, while her husband, Jake, was there carrying out ethnographic work.

She mainly did drawings and water color townscapes as well as a series of portraits of local people.

Some of these works, as well as the photographs she took, formed the basis of later prints and major collages, such as Processione (1987/88), based on a procession of the Madonna she had photographed.

An exhibition of Shirley’s work from Nocara was held in the village in the early 1980s. Some years ago, she donated many of the art works she had created there to the town, where they are displayed in the local museum.

I don’t have all the details yet, but it will be a one-day event, that afternoon/evening, with a speaker from the University of Cosenza.

Shirley spent several periods of time painting in Nocara, while her husband, Jake, was there carrying out ethnographic work.

She mainly did drawings and water color townscapes as well as a series of portraits of local people.

Some of these works, as well as the photographs she took, formed the basis of later prints and major collages, such as Processione (1987/88), based on a procession of the Madonna she had photographed.

An exhibition of Shirley’s work from Nocara was held in the village in the early 1980s. Some years ago, she donated many of the art works she had created there to the town, where they are displayed in the local museum.

Friday, July 16, 2010

Centropa -- Travel Column on Vienna

Here's my centropa.org travel column on Vienna.

Vienna

by Ruth Ellen Gruber

Vienna looms large in Jewish history and memory.

The imperial Habsburg capital was the vibrant hub of a vast, multi-national Empire that stretched across Europe and encompassed a colorful and sometimes contentious mix of peoples, languages, religions and local cultures.

Jews lived here for centuries. Surviving pendulum-swing periods of tragedy and triumph, prosperity and persecution, they made key contributions to the cultural, economic and intellectual development of the city.

Nineteenth and early 20th century Vienna in particular was home to some of Europe's most influential artists, authors, musicians and thinkers -- from the writers Joseph Roth, Arthur Schnitzler and Stephan Zweig, to the composers Arnold Schoenberg and Gustav Mahler, to the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud. Vienna was also the cradle of some of the icons of popular culture: the filmmaker Billy Wilder grew up in the city, and the novelist Vicki Baum, the author of Grand Hotel and other best-sellers, was born here and wrote about her Viennese childhood in her memoirs. "To be a Jew is a destiny," she once said.

The Holocaust swept this world away. But monuments, museums and other vestiges of this long and creative Jewish presence can be found in many parts of the city. What's more, Vienna is home, now, too, to a new flowering of Jewish life and creativity, both religious and secular. Vibrant schools, synagogues and other Jewish centers bear living witness to a remarkable Jewish rebirth in the decades since the Shoah. And Jewish writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers are putting their stamp on contemporary culture.

Visitors to Vienna can get a taste of both worlds. Most Jewish historical sites and monuments, as well as most active synagogues and Jewish centers, are located in central parts of the city, embedded in a historic urban setting that conjures up the grandeur of the past amid the contemporary bustle of modern-day life.

The following itinerary highlights some of the most important (and most easily visited) Jewish sights, but still, alas, gives only a brief taste of the richness of Jewish experience in the city.

The Jewish Museum

Vienna's Jewish Museum is a good place to start for both an overview of the city's Jewish history and a taste of today's Jewish cultural offerings. The Museum's main location opened in 1993 in the Palais Eskeles, a downtown mansion at Dorotheergasse 11, in the heart of Vienna's First District. Its unusual exhibition arrangement offers a unique view of Jewish history and memory.

On the ground floor there a display of Judaica objects from a noted collection is paired with an artistic installation reflecting Viennese Jewish history by the American artist Nancy Spero. Upstairs, there is another display of Judaica -- in what is called the "Viewable Storage Area." Here, massed together on shelves, are hundreds and hundreds of ritual and every day objects, many of them salvaged from destroyed households, synagogues and prayer rooms. Some of the silver objects are charred and smoke-stained from the fires of Kristallnacht. The intent of showing the objects this way is to underscore the pride and prosperity of the Jewish community, as well as the extent of the destruction.

The permanent historical exhibition is something quite different. It comprises no physical objects at all. Instead, it consists of 21 holograms, arranged in a bare room. Each is a sort of holographic still life that represents a specific stage, facet or theme associated with Austrian Jewish history and the relationship between Jews and Austrian society. These themes include "Houses of God," "Zionism," "Anti-Semitism," "Loyalty and Patriotism," "From Historism to Modernism," "Shoah," "Vienna Today Š", "Banishments" and "Fin de Siecle."

Key components of the museum are also a comfortable cafe -- reminis cent of the coffee houses where Jewish writers, intellectuals and luftmenschen alike once passed long hours -- and a well-stocked bookstore featuring hundreds of titles of Jewish interest or by Jewish authors on a wide range of topics.

The Jewish Museum also has a branch at Judenplatz, the heart of Vienna's medieval Jewish quarter, which forms part of a complex inaugurated in 2000 that also includes a Holocaust memorial commemorating the 65,000 Austrian Jews killed in the Shoah and a Holocaust documentation center.

Vienna's flourishing medieval Jewish community was snuffed out in 1420/21 by persecutions that culminated in expulsions, murders and the torching of the synagogue on Judenplatz, with Jews inside. A 15th century plaque in Latin on the house at Judenplatz 2 still celebrates this, reading, in part: "Thus arose in 1421 the flames of hatred throughout the city and expiated the horrible crimes of the Hebrew dogs."

The underground remains of the synagogue were discovered during excavations in the 1990s and these now form the core of the Judenplatz Jewish museum, along with a multi-media exhibit about Medieval Jewish life.

Above, at ground level, stands the Holocaust Monument, a massive cube of reinforced concrete that dominates the square. Called the Nameless Library, it was designed by the British sculptor Rachel Whiteread and takes the form of an "inside-out" library -- rows of books with their spines facing inwards. Also inscribed are the names of the sites where Austrian Jews were killed.

Not far away, near the Opera House, stands a big Monument against War and Fascism, by the artist Alfred Hrdlicka. Among several big symbolic sculptures it incorporates a bronze sculpture of a bearded Jew on his knees, almost prostrate, covered by barbed wire, forced to scrub the street. And as you walk about parts of the city, keep an eye out for the Stolpersteine, or stumbling blocks -- these are brass cobblestones put down to mark the houses where Jews and others killed by the Nazis once lived, as part of a commemorative project by the artist Gunter Demnig.

What is today Vienna's Second District, across the Danube Canal from the inner city, was long a Jewish neighborhood. Before World War II about 60,000 Jews -- one-third of Vienna's Jewish population -- lived here, and the district was home to so many synagogues, Jewish theaters, schools and other Jewish institutions, that it was dubbed "The Matzo Island." Most of these sites no longer exist, but a number of plaques AND STOLPERSTEINE, OR COMMEMORATIVE STUMBLING BLOCKS, evoke the neighborhood's Jewish history, and new synagogues and other institutions make it a center of Jewish life.

The Main Synagogue

The Stadttempel, Vienna's Main Synagogue, is located on sloping Seitenstettengasse. Designed by the architect Josef Kornhausel, it was built in 1824-26. From the outside, it looks like a plain, anonymous building -- in fact, many synagogues in Europe were hidden behind featureless outer walls. This was either for protection or in compliance with edicts that allowed direct access to the street only for churches. This in act saved the synagogue during Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938; it was not torched for fear that the entire block could go up in flames. All of the other nearly 100 synagogues and Jewish prayer houses in Vienna were either destroyed or severely damaged. What sets the synagogue apart these days are the armed guards outside.

Inside, the a graceful oval sanctuary is encircled by two tiers of women's galleries and topped by a sky-blue domed ceiling sprinkled with gilded stars. A gilded sunburst surmounts tablets of the Ten Commandments above the ark. At Jewish holidays, every seat is full, and the building complex also houses the Jewish communal offices and archives.

Cemeteries and other sights

What is today Vienna's Second District, across the Danube Canal from the inner city, was long a Jewish neighborhood. Before World War II about 60,000 Jews -- one-third of Vienna's Jewish population -- lived here, and the district was home to so many synagogues, Jewish theaters, schools and other Jewish institutions, that it was dubbed "The Matzo Island." Most of these sites no longer exist, but a number of plaques evoke the neighborhood's Jewish history, and new synagogues and other institutions make it a center of Jewish life.

Vienna has several Jewish cemeteries that are worth exploring, both for their historical importance and for the artistic beauty of the tombs.

The vast Zentralfriedhof or Central Cemetery, at Simmeringer Hauptstrasse 234 in the 11th district, was consecrated in the 1870s and has an extensive Jewish section where about 100,000 people are buried. There are many stately tombs and mausolea, testifying to the prosperity of the community.

One of the easiest cemeteries to visit -- and also one of the most fascinating -- is the Rossau cemetery, the oldest preserved Jewish cemetery in Vienna. It is entered by walking straight through the lobby of a modern municipal old age home at Seegasse 9, in Vienna's 9th district, a five minute walk from the Rossauerlaende U-Bahn stop. (It may seem a cruel juxtaposition to enter a cemetery through an old-age home, but from 1698 to 1934 this was the site of a Jewish hospital.)

The Rossau cemetery is believed to have been founded in 1540 -- the oldest legible stone dates from 1582 -- and it operated until 1783, when the Emperor Joseph II issued a decree banning burials inside what today is the "Gurtel" ring around inner Vienna. Many 17th and 18th century luminaries were buried here, including the financiers Samuel Oppenheimer and Samson Wertheimer.

According to the useful guidebook Jewish Vienna published in 2004 by Mandelbaum Verlag, some of the few local Jews still living in Vienna in 1943 managed to rescue some of the tombstones, either burying them on the spot or transporting them to the Central Cemetery and burying them there.

In the mid-1980s, after the discovery of these stones, the cemetery underwent a full restoration -- and the surviving stones were set up in their original places thanks to a map of the cemetery that had been made in 1912. Many of the stones are massive and feature elegant calligraphy, lengthy epitaphs and some vivid carving of Jewish symbols and floral and other decoration, similar to that on tombs in the Jewish cemetery in Mikulov, Czech Republic, and elsewhere in Moravia. Fragments that could not be put together were used to construct a memorial wall, similar to those that exist in other countries at restored cemeteries. Wertheimer's tomb, a white mausoleum with carved end pieces, is the cemetery's most imposing.

The Rossau Cemetery is a short walk from the Sigmund Freud Museum, at Berggasse 19, which occupies the building where Freud lived and worked from 1891 until 1938, when he fled to England to escape the Nazis. The museum includes original furnishings, some of Freud's antiquities collection and library, films and other material that provide insights into his life and work. The museum also houses a collection of contemporary art and a research library.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)