Old-New synagogue. Photo (c) Ruth Ellen Gruber

Here below is my

column on Jewish Prague for centropa.org.

I've been writing about Jewish Prague for, yipes, decades....my first experience there dates back to (yipes again) 1966, when I spent the summer in then-Czechoslovakia with my family. My dad had brought a group of students over from the U.S. and was leading the first American archeological dig in CZ since before WW2. They were digging out in Bylany, a village near Kutna Hora, and one of my brothers stayed there and worked with the crew.

In 2007, soon after my mother's death, I took Dad to revisit the site in Bylany -- I reconnected in 1989 with the archeologists we had known in '66 and we remain close.

In 1966, my mother and youngest brother and I stayed in Prague. Sam and I wandered around the city, visiting the tourist sites and just soaking in the atmosphere, and it is this experience that gave me my deep interest and connection with eastern and central Europe. It was then, indeed, that I had my first contact with Europe's "imaginary wild west" -- when Sam and I attended a 10 a.m. showing in the Kino Sevastopol of Old Shatterhand, one of the movies based on the Karl May characters. I fell in love (like many girls in central Europe at the time) with Pierre Brice, the French actor who played the Apache chieftain Winnetou... I bought postcards of him and also cut out his picture from magazines. I also got a crush on the singer Waldemar Matuska, who performed, among other things, American folk songs in Czech and starred in a Czech language production of Rose-marie (he played the Mountie, the role playedin the movie by Nelson Eddy, my mother's childhood fave). Matuska, who died last year -- and whom I met at a Czech country festival in 2004 --also had a role in the great Czech Western spoof Lemonade Joe.

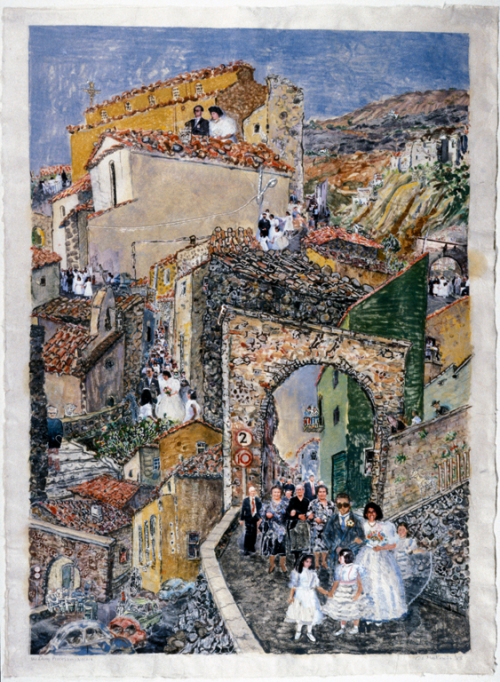

While in Prague we visited at least some of the Jewish sites -- and my mother,

the artist Shirley Moskowitz, painted a wonderful picture (later developed into a print) of the Old Jewish Cemetery.

(c) estate of Shirley Moskowitz

Here's the centropa article. It picks up on the idea of Jewish Prague as a series of concentric circles that I wrote about at length in my 1994 book

Upon the Doorposts of Thy House: Jewish Life in East-Central Europe, Yesterday and Today.

Prague

by Ruth Ellen Gruber

PRAGUE -- Lying between the Vltava River and the Old Town Square, Prague's medieval "Jewish Town," Josefov, is one of the most popular attractions in a magical "golden city" that draws millions of tourists a year. Here, amid historic synagogues, the Old Jewish Cemetery, the Jewish Town Hall and other major sights, is the Ground Zero of Jewish Prague: the stomping ground for heroes and villains and the evocative background setting for a host of old legends, not to mention the cradle of present-day Jewish life. Here, Jewish heritage and legacy are cultivated and exploited as an integral part of the ancient city. At peak season, tourists swarm through the district, making it sometimes difficult to navigate the cobbled streets, and souvenir hawkers sell everything from miniature golems to embroidered kippot.

I imagine the Jewish presence in Prague as a series of concentric circles centered on this medieval ghetto area and then expanding outward, like widening ripples of water, to the edge of the city and beyond. Physical sites, as well as Jewish memory and contemporary Jewish life, are concentrated in the innermost circle: there are a Jewish education center, kosher facilities and Jewish communal offices, and regular services take place in several venues. But there are many places of Jewish interest well away from the city center, too. These are much less visible and well off the beaten track of most visitors to the city, but they, too, form an integral part of the Jewish experience in Prague. The following itinerary will let you sample some of these outer circles of Jewish history and culture as well as the city's inner core.

The Inner Circle

Tourists aside, Prague's old Jewish quarter today bears very little resemblance to the dense welter of narrow alleys, tiny squares, dark passageways and crowded courtyards where generations of Jews were compelled to live from the Middle Ages to the mid-19th century, when the Habsburg monarchs granted them civil rights. After emancipation, many Jews moved out, and Jewish Town became a slum. An urban renewal project in the late 19th century swept away almost everything but a handful of synagogues and a few other historic sites, and the medieval ghetto was replaced by the handsome complex of buildings we see today. On the façade of the building at Maiselova 12, across from the Old-New Synagogue, you can see Jews symbolized by the star of David, money and stereotype profiles.

Jewish Town is still, though, where the city's main Jewish sights are concentrated. And if you can brave the crowds, you will see some of the finest and best preserved and presented Jewish heritage sites in Europe.

These include the 13th-century Old-New (or Alt-neu) Synagogue, the oldest synagogue in Europe still in use. Built about 1270, the compact Gothic building has a high peaked roof and distinctive brick gables. The twin-naved sanctuary features soaring Gothic vaulting and a central bimah enclosed by a late Gothic iron grille. Carvings of grape vines surround the Ark.

Across narrow Cervena alley is the High Synagogue, built in 1568, which, like the Old-New Synagogue, is today an active house of prayer and study. Right next door to the High Synagogue is the Jewish Town Hall (entrance at Maiselova 18), which still serves as the headquarters for Jewish community offices and activities. Built in the 1560s, the Jewish Town Hall is one of the landmarks of the Jewish quarter, with a distinctive tower and big clock with Hebrew letters, that seems to run backwards.

Prague's Jewish Museum occupies several historic synagogue buildings in the district. The museum was originally founded in 1906 to preserve items from the synagogues that were demolished in the urban renewal clearance of the old ghetto. Most of its collections, however, come from the more than 150 provincial Jewish communities in Bohemia and Moravia that were destroyed by the Nazis. The Nazis brought the loot to Prague, and even during World War II used the empty synagogues to exhibit precious relics of the people they sought to annihilate. The museum was run by the communist state after World War II, but it was returned to Jewish administration in 1994.

Today, the collections are displayed thematically in some of the historic synagogues, and these synagogues themselves form key components of the museum complex.

The Maisel Synagogue (Maiselova 10), originally built in 1590, houses an exhibition on Czech Jewish history from medieval times until the end of the 18th century. Among its displays are stunning silver ritual objects. The Spanish synagogue (entrance from Vezenska street), was built in elaborate Moorish style in 1868 on the site where Prague's oldest synagogue once stood. It houses the second part of the Jewish Museum's historical exhibition, detailing the Jewish experience in Prague from the late 18th century to the present. Next door, the Robert Guttman Gallery hosts temporary exhibitions, mainly of contemporary art. The Museum's "Jewish Customs and Traditions" exhibition is housed in the Baroque Klausen synagogue (U Stareho Hrbitova 1), built in the late 17th century. The Pinkas Synagogue (Siroka 3), built in 1535 as a private prayer house for the wealthy Horowitz family, is a memorial to the Jews from Bohemia and Moravia who were killed in the Holocaust. The names and dates of birth and death of all 77,297 victims are inscribed on the walls of the sanctuary. Its upper floor houses an exhibit of materials from the Holocaust period, in particular from the Terezin ghetto, including drawings and poems by the children there.

The unforgettable Old Jewish Cemetery (entrance from the Pinkas synagogue courtyard) is also part of the Museum. Here, some 12,000 tombstones crowd together in bristling clusters, tilted crazily and sunk into the earth. Founded at the beginning of the 15th century, the cemetery was in use until 1787: Lack of space caused graves to be placed on top of each other, and the cemetery's unique appearance has inspired artists and poets for centuries. The oldest identified gravestone is that of Avigdor Kara, from 1439. The Old Cemetery's Ceremonial Hall (U Stareho Hrbitova 3), built in 1911-1912, houses an exhibition on Jewish funeral practices.

Many famous Prague Jews are buried in the Old Jewish Cemetery, including the 16th-century financier Mordechai Maisel and the legendary Rabbi Judah ben Bezalel (c. 1525-1609), a scholar and educator known as the Maharal ("most venerated teacher and rabbi"). Rabbi Loew's tomb is a place of pilgrimage, where pious Jews and tourists alike leave prayers and supplications written on slips of paper.

Many legends grew up around Rabbi Loew over the centuries -- the most famous has it that he created the Golem -- an artificial man made of clay and magically brought to life to protect the Jews. The Rabbi and the legends about him became so deeply rooted in Prague folk culture that a statue of him was included as part of the decoration of the New Town Hall that was built in 1910.

The author Franz Kafka (1883-1924) is also intimately connected with Prague's Jewish Town. He was born on the edge of the Jewish quarter and spent much of his life in and around the district. There is an extensive Franz Kafka Museum at the Hergetova Cihelna, on the Malá Strana bank of the Vltava, as well as a small exhibit at U Radnice 5 (or, Franz Kafka Square), near the Old Town Square, on the site where Kafka was born. A bust of the author stares out from the street corner there, and, not far away, a monument to Kafka stands next to the Spanish Synagogue. This is a 12-foot sculpture that shows a tiny figure of Kafka perched atop an empty suit of men's clothing that seems to be walking. Kafka himself is buried in Prague's New Jewish Cemetery.

Just outside the Jewish Quarter, one of the sculptures that line the tourist-choked Charles Bridge across the Vltava River is a big figure of the crucified Jesus with gold letters spelling out the Hebrew words Kadosh, Kadosh, Kadosh Adonai Tzvaot (Holy, Holy, Holy Is the Lord of Hosts) affixed above it. In the 17th century, the Jewish community was forced to pay for these words to be placed on the cross as punishment for the alleged desecration of the crucifix by a Jew.

Outer Circles

The lavishly ornate Jubilee Synagogue, located at Jeruzalemska street 7 near Wenceslas Square, was designed by the prolific architect Wilhelm Stiassny and built to replace three synagogues destroyed in the clearance of the old ghetto. It is still used for services. Formally called the Emperor Franz Joseph Jubilee synagogue, it was named in honor of the Habsburg ruler and officially dedicated in 1908 -- the 60th anniversary of his reign. Franz Joseph was a respected, even beloved, figure among Jews -- it was during his reign that Jews were granted full emancipation -- and even today there is a portrait of him hanging in the function room of the Jewish Town Hall. The Jubilee Synagogue incorporates Moorish, Byzantine and art nouveau elements, with a striped façade, towers, arches and a rose window incorporating a star of David.

Several other synagogues still stand in Prague, too. Among them is the stark-looking synagogue in the Smichov district, at the corner of Plzenska and Stroupeznickeho streets, which was built in 1863 and totally remodeled in the Functionalist style in 1931. It now serves as the archive of the Jewish Museum. The neo-Romanesque Liben Synagogue, at the Palmovka metro station, was built in 1860 to replace an earlier synagogue, built in the 16th century. After World War II it was used as a warehouse, but it was restored in the 1990s and now serves as a venue for cultural events. In the outlying suburb of Michle, the synagogue (on u Michelskeho Mlyna street) now serves as a church.

There are several Jewish cemeteries in outer parts of Prague. Two of them are particularly significant and easily visited.

The New Jewish Cemetery, located at the Zelivskeho metro stop in eastern Prague, was founded in 1890 next to the city's main Olsany cemetery complex, and is still in use. The wealth and importance of the Jewish community in the late 19th and early 20th century can be seen in the ornate ceremonial hall and the many imposing family tombs and other monuments. A white, crystal-shaped stone marks Franz Kafka's grave, and a plaque there commemorates Kafka's three sisters, who were killed in the Holocaust.

The Jewish Cemetery in Zizkov, not far from the New Cemetery, near the Jiri z Podebrad metro stop, now forms part of the Jewish Museum. Opened in 1680 as a graveyard for Jewish victims of the plague, it was the main Jewish burial place in Prague between the closure of the Old Cemetery in 1787 and the opening of the New Cemetery. Most of the cemetery was demolished in the 1950s, and a huge, futuristic-looking television tower was erected on the site in the 1980s: a number of sculptures of crawling babies were placed on the structure about ten years ago and add to its weirdness. The surviving section of the cemetery is fenced off and is only open limited times during the week, but it can easily be viewed from outside. It includes the imposing tombs of important personalities, including the influential Prague Chief Rabbi Ezekiel Landau (1713-1793).

There is also a walled-off Jewish cemetery in the Liben district, between Na Malem Klinu and Strelnicni streets, as well as an 18th-century Jewish cemetery in Urhineves, an outlying suburb in southeast Prague. Located at the end of Vachkova street, it was cleaned up and restored in the mid-2000s.